Running on meadows and searching in landing nets – surveying butterflies and wild bees on a restored grassland site

2nd logbook entry in the series "How does scientific fieldwork actually work?"

What do you think of when you hear the term species-rich grassland? It wouldn’t be surprising if a wild bee or butterfly came to your mind. We associate these insects with species-rich meadows and pastures for good reason: They find sufficient and diverse food and habitat there thanks to the rich abundance of flowers. As a result, and as they react quickly to disturbances in their habitats, they are good indicators of the species richness of grasslands. It is precisely for this reason that we use them alongside the analysis of soil and vegetation to analyse the ecological restoration success of our grassland study sites.

In the first post of our fieldwork series, we already introduced the project setup and the investigation of the soil of our grassland sites. In this post, we provide an insight into the survey of butterflies and wild bees. As the soil, these are also being surveyed on all restored study sites and reference sites and should contribute to answering the question of what leads to success in grassland restoration in Germany. This clarifies the reason for surveying butterflies and wild bees, but what does such a survey look like in practice?

Logbook entry: Recording wild bees and butterflies on a study site

June 05, 2023

We’re back at our restored study site N_DWQ, only this time it’s summer and quite a sunny day as well – in a way, it has to be. It’s not the first time we’ve been here to record butterflies and wild bees: The butterfly and wild bee surveys are carried out on all sites every month between May and August, i.e. four times per site, in order to get an impression as complete as possible. Compared to soil and vegetation, butterflies and wild bees are much more sensitive, so certain conditions must be met for them to be recorded: It must not be raining, it must be warm enough, and ideally not too cloudy (this means at least 13°C, or 17°C if it is more cloudy). In addition, it must not be too windy (maximum wind force 3). These conditions were more than met on the day of our survey and our site was covered in bright sunshine.

On the landing nets, get set, go?

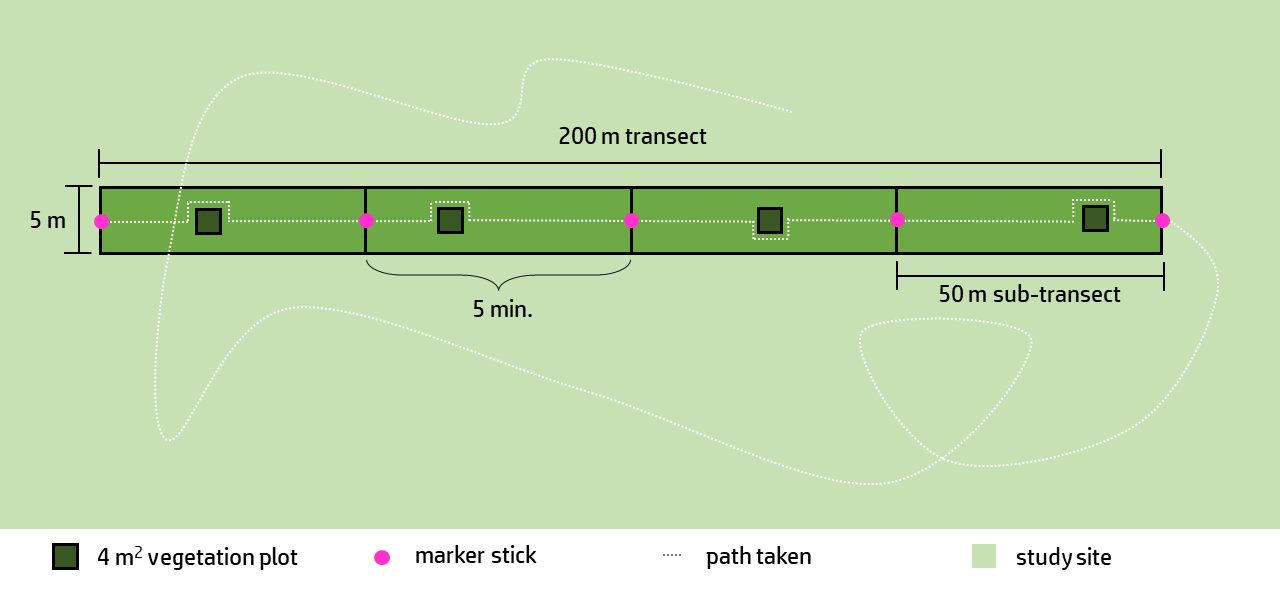

At the beginning of the survey, the 200 m long and 5 m wide transect, which had already been measured with GPS during the soil sampling, is marked with sticks in exactly the same way with its four 50 m long sub-transects. As with the soil sampling, this serves the purpose of comparability. The survey is carried out according to sub-transects and time. For both the butterflies and the wild bees, each sub-transect is surveyed for 5 minutes and then the entire area is surveyed twice more (see Figure 2). The recording of wild bees and butterflies is carried out simultaneously by two people, each on different sub-transects and with sufficient spatial and temporal distance. This is to prevent the animals from being startled by the other recording, which could lead to misleading results. The actual recording of the animals is carried out with landing nets but differs slightly between the two insect species.

Surveying butterflies – About racing on meadows and pastures

To be precise, not only butterflies but also burnet moths are included in this survey, as they, like butterflies and wild bees, are also good indicators of restoration success and are all diurnal moths. The recording starts at one of the marker sticks, equipped with a stopwatch, a landing net, and a bag with an Aerarium (a flexible cube made of a fine net and wire in which the captured butterflies can be placed, see Figure 3), all kinds of identification aids and other useful things for identifying the butterflies. The marker sticks mark the beginning and end of each sub-transect in the middle (see Figure 2). The path to the next marker stick should now take exactly 5 minutes. And it is really only about the time for the path, as soon as a butterfly is spotted, the time is paused. This applies to all butterflies that are within 5 m to the front and 2.5 m to each side in the sub-transect or flying along it. Then it’s time to stop, drop everything, and run after the butterfly with the landing net – literally, the bag marks the point at which you can then continue. Once the butterfly has been caught, it is placed in the aerarium to make it easier to see and to prevent the same butterfly from being recorded more than once.

It is then identified there and added to the recording sheet. In addition, its behavior is noted: Was it flying, was it sitting, was it sucking nectar (if so, on which plant), was it mating or fighting for territory with another butterfly, or has it just laid eggs? This helps to assess how attached the butterfly is to the respective area: Did it just happen to fly past and actually only want to go to the rapeseed field next to it or has it found food in the area itself and is deliberately staying there? Once everything has been noted, you start again at the point where you stopped the time and the time continues to run until the next butterfly sighting. This process is also repeated for the other three sub-transects and the two follow-up walks. At the end of the survey, the butterflies are released back into the wild.

Surveying wild bees – buzzing chaos in the landing net

Wild bees are collected according to the same principle, but here the vegetation is only netted over a width of 1 m on either side of the centre. Afterwards, the contents of the landing net with all the insects captured along the way are inspected. All wild bees are collected in individual glass tubes and recorded on the recording sheet. With the exception of the bumblebees, they are taken away, prepared, and sent to a wild bee specialist who identifies the bee species. This is because the identification of wild bee species is often very difficult and can only be carried out by specialists. Bumblebees are an exception, as they can also be easily identified in the field and are therefore released again after being identified.

Analysing flower cover and vegetation height

In addition to the butterfly and wild bee survey, the flower cover in the vegetation plots (a 4 m2 area on each sub-transect used for the vegetation survey, see Figure 2) is recorded, as well as the vegetation height distributed over the entire transect. For this purpose, each vegetation plot is divided into four 1 m2 parts, each of which is marked and photographed from above. This is used later to determine the flower cover. The vegetation height is measured three times per sub-transect and thus 12 times per transect. This data can later be combined with the wild bee and butterfly data to analyse the influence of flower supply and vegetation height on butterflies and wild bees.

What could we net? – Results of our survey

We were able to find several butterflies and wild bees on our site today (see Tables 1 and 2). Amongst the butterflies, there were many Common blue butterflies, some Small heaths, and even two Glanville fritillaries (shown on the cover photo), which are on the Red List and classified as endangered. Among the wild bees, there were many Red-tailed, Red-shanked, and Broken-belted bumblebees, as well as some Buff-tailed bumblebees and Common carder bees. The remaining wild bees are still being identified.

Table 1: Butterflies recorded at study site N_DWQ on 05/06/2023.

| Butterflies | |||

| Transect section | Species name | Number | Behaviour |

| A1 | Coenonympha pamphilus (Small heath) | 1 | sitting |

| A1 | Coenonympha pamphilus (Small heath) | 1 | flying |

| A1 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 1 | sucking on Lotus corniculatus (bird’s-foot trefoil) |

| A1 | Lycaenidae (Gossamer-winged butterfly) | 1 | fliegend |

| A1 | Lycaenidae (Gossamer-winged butterfly) | 1 | sucking on Lotus corniculatus (bird’s-foot trefoil) |

| A1 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 1 | Balzflug/Revierkampf |

| A1 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 2 | flying |

| A2 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 1 | sucking on Lotus corniculatus (bird’s-foot trefoil) |

| A3 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 6 | flying |

| A3 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 1 | sucking on Trifolium pratense (Rotklee) |

| A4 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 2 | flying |

| N1 | Melitaea cinxia (Glanville fritillary) | 1 | sitting |

| N1 | Melitaea cinxia (Glanville fritillary) | 1 | flying |

| N1 | Coenonympha pamphilus (Small heath) | 4 | flying |

| N1 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 2 | flying |

| N2 | Polyommatus icarus (Common blue butterfly) | 3 | sitting |

| N2 | Coenonympha pamphilus (Small heath) | 2 | flying |

Table 2: Wild bees recorded and determined in the field at study site N_DWQ on 05/06/2023.

| Wild bees | |||

| Transect section | Species name | Number | Sex |

| A1 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 7 | female |

| A2 | Bombus lucorum agg. (Buff-tailed bumblebee) | 4 | female |

| A2 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 3 | female |

| A2 | Bombus pascuorum (Common carder bee) | 1 | female |

| A3 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 3 | female |

| A4 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 1 | female |

| N1 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 8 | female |

| N1 | Bombus lucorum agg. (Buff-tailed bumblebee) | 1 | female |

| N2 | Bombus lapid./rud./soro. (Red-tailed/Red-shanked/Broken-belted bumblebee) | 5 | female |

| N2 | Bombus pascuorum (Common carder bee) | 2 | female |

| N2 | Apis mellifera (Honey bee, does not belong to the wild bees) | 1 | female |

This data is combined with the other data from the surveys, sites, and model regions and is then statistically analysed. The aim is to find out, for instance, which factors determine the success of restoration for butterflies and wild bees, whether certain restoration methods have a particularly positive effect on wild bees and butterflies, and what role the age of the site and its management play. These findings, together with the other results obtained in the ecological part of the project, will then be incorporated into the overall analysis of the question of what leads to success in grassland restoration in Germany.

You can gain more insights into the ecological fieldwork in the article on soil sampling on our sites and the article on vegetation surveys that will follow soon.

Lea Pöllmann

I am studying environmental and sustainability sciences with a focus on ecology and nature conservation at the Leuphana University of Lüneburg. I am particularly interested in ecosystem functions and interactions and how we can connect them with our social systems in a sustainable and mutually beneficial way. At Grassworks, I mainly work in outreach and am writing my thesis in the ecological research component.

Leave a Reply